I.

Blue Collar (1978) follows three autoworkers in Detroit. Desperate, financially struggling, and feeling trapped in their demanding and dangerous jobs, the men rob their office’s safe. Instead of money, they find evidence of corruption within their union’s leadership. Thwarted in their attempt to use the evidence as blackmail, they face a series of threats that ultimately lead to one man’s death. He is given orders to work on a car in the factory paint booth, and once inside, another worker parks a forklift outside barring the only exit. The ceiling nozzles suddenly turn on, emitting a mist of dark blue paint. Unable to shut them off, unable to escape, he claws at the walls leaving violent streaks of cobalt. Blue splatters soil his white painter’s suit. His cries for help are inaudible against the incessant hum and din of the factory. The blue-collar worker suffocates in a chamber of blue noxious fumes.

In the ruling of his death as an accident by the factory leadership, it becomes apparent the auto company, the union, and the police are all in collusion and will go to any length to conceal corruption and maintain power. Instead of avenging the murder of their friend, the two men are systematically turned against each other. All fraternal bonds crumble under paranoia and fear. No man nor allegiances among men can withstand the power of the institution according to Blue Collar. Their bodies and spirits are broken down on the line. Their cunning and creativity eventually extinguished. Their pleasures and aspirations bent and buckled to American corporate and consumerist conformity.

“Got a house. Fridge. Dishwasher. Washer. Dryer. TV. Stereo. Motorcycle. Car. Buy this shit. Buy that shit. All you got’s a bunch of shit.”[1]

While scouting locations for the film, director Paul Schrader sought real working auto factories for the set. Every place turned him down except for Checker Motors Corporation in Kalamazoo, Michigan about 150 miles west of Detroit. The reason Checker accepted was due to tension and unrest among their workers, and the managers hoped that movie production might distract and settle them. Life imitates art.

“If the company can’t crush a noisome fly, it can do something far worse. You’ll see. Keep those cabs rolling out. Never stop the anvil chorus. Grease the gears. Those Checker Cabs. Was that a conscious choice on Schrader’s part? The fact that these cabs, the same model Travis Bickel piloted in Taxi Driver, came from a hot, hopeless hell like the factory in Blue Collar? Where every rivet was fastened by someone with murder on their minds? Every windshield tamped into place by someone who wanted to blow up the world? Every steering column and gas pedal affixed by the damned? It’s as if the metal, rubber and fuel themselves were infused with rage. Bickel never stood a chance.”[2]

II.

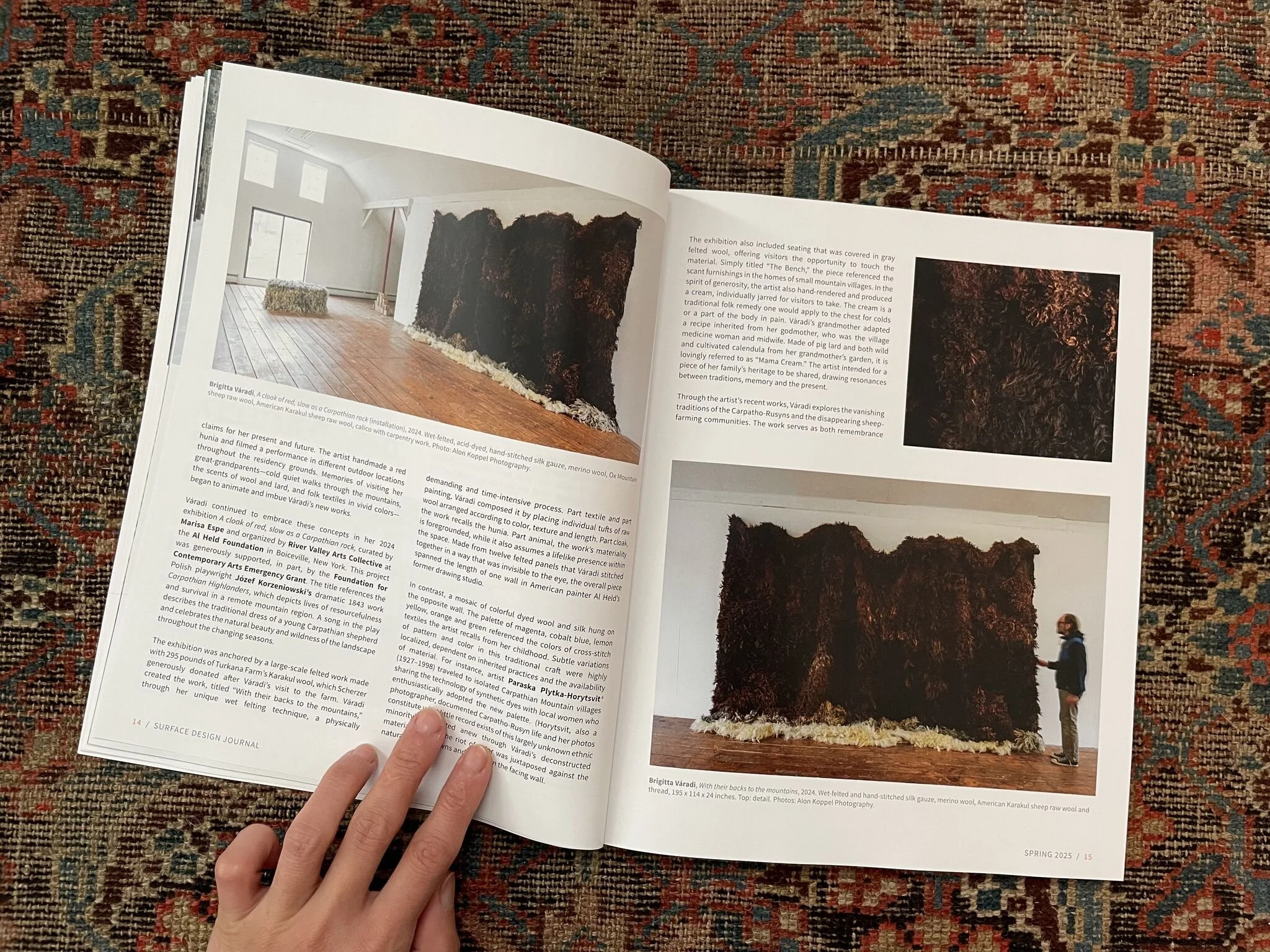

Artist Cudelice Brazelton IV’s practice blends material experimentation and conceptual investigations with work that spans sculpture, installation, painting, and sound. His work gathers resonances across aesthetic and spatial modalities by putting text, image, material, sound, and space into generative confrontations within the works themselves and with the viewer.

The work, like the artist, moves between worlds, airing both the friction between and the complementary qualities shared among the hair salon, the barbershop, the factory, the tailor, the club, the white cube, the street, the studio, the home. Each world nurtures languages, styles, behaviors, attitudes, and gestures of its own from which residual iconography flows and percolates with those of other commingling worlds. Never fully under the gravitational pull of one more than another, the artist wields collage to describe intersections, overlaps, and influences. Brazelton reconciles divergent methods. On the one hand, the specificity of a faux leather’s color and grain has the ability to instantly transport viewers via haptic memory. On the other hand, abstraction abounds, and some references don’t readily reveal themselves—they’re not for everyone anyway.

Brazelton has consistently explored techniques of assemblage. Here, the found object is not fetishized as an exhibit of authenticity purely extracted from the so-called real world. Nor is the found object romanticized like ruin porn, a stand-in for abject detritus. It is rather material and psychic texture, sometimes in harmony, sometimes dissonant among other textures. In a single composition, some things are cut and fall satisfactorily, others bend against the grain in edgy tension. Some things are singed, some things shine, some things would cut to the touch. A texture, or word, or image is like a clue, a cue, a knowing nod to the environs in which it orbits.

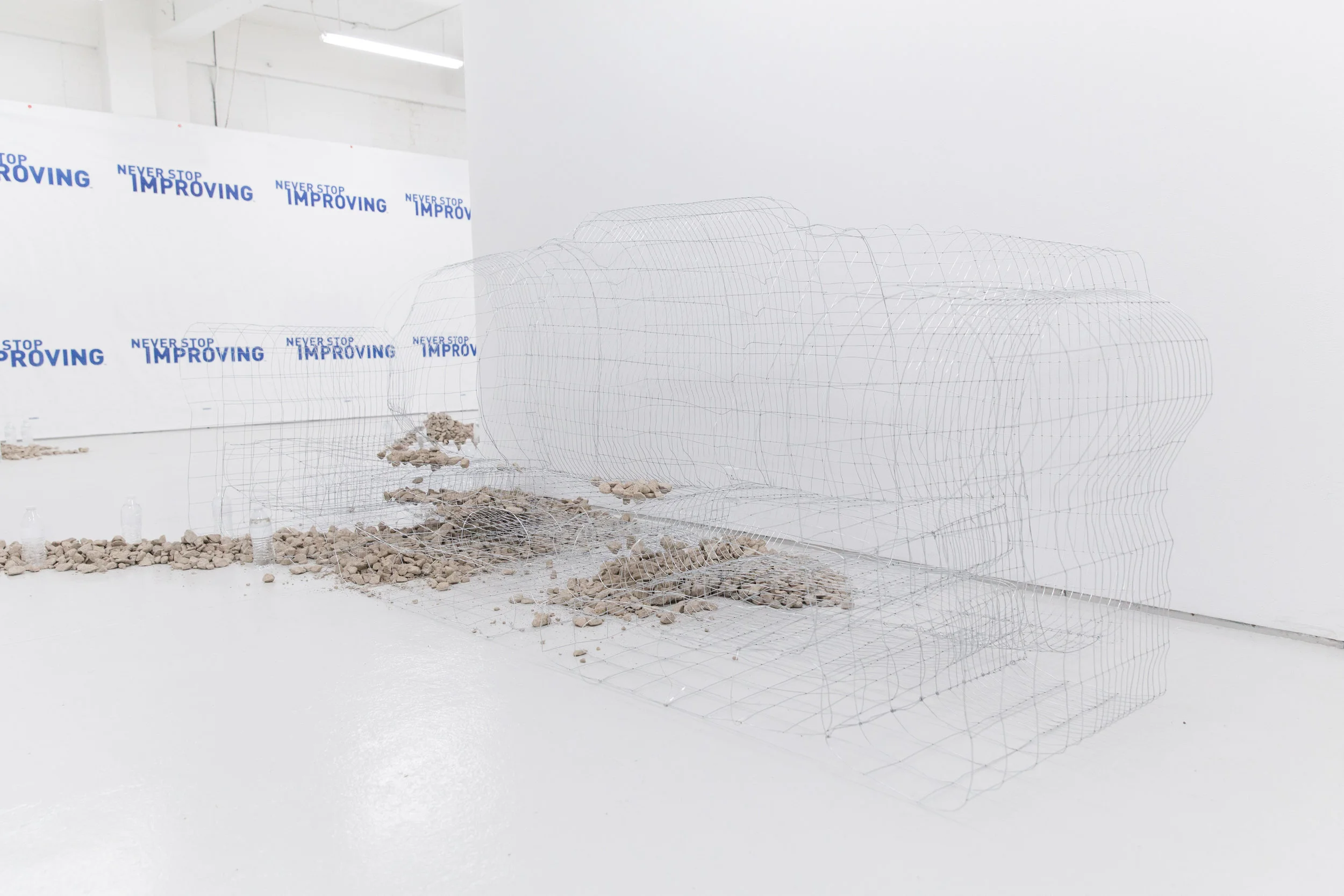

At the same time, Brazelton’s works remain deeply responsive to the spaces they inhabit. Burned contours round a corner. Steel rods with modeling clay and graphite scale a wall or suspend from the ceiling. Unspooled wire scrambles across the floor. Lines of thread trace baseboard molding. Getting through the door is complicated. To occupy Brazelton’s installations is like an exercise in potential energy, as if the room could come alive, the temporarily dormant components in each work animated, setting off a Rube Goldberg-like machine of steel, plastic, paint, wire, magnets, fake leather, cardboard, wood, and paper. Measured and diagrammatic in the way the works relate to each other, to the space, and to the viewer, the overall gestalt impresses as a total system according to Brazelton’s unique lexicon.

The artist often installs his work in ways that interrupt views or frame perspectives, calling attention to the negative space. The work charges everything around it, like microclimates simultaneously supplying and extracting from the sculptures, paintings, and installations. It’s an atmosphere thick with history, sociality, and in a sense the artist’s sympathy. Without wading too deep into the waters of autobiography, Brazelton’s upbringing in the rust belt of the United States, his mother’s expertise as a cosmetologist, his time spent working in a steel factory and running a DIY space, his expat status as a Black American in Germany yield certain techniques instead of topics, sensibilities instead of subject matter.

Much in the same way, Schrader’s Blue Collar generally avoids straightforward or trite depictions of identity. Layered dynamics complicate the essentialized portrayal of a worker in America, of a Black man in America, of a white man in America. These portraits include race, class, labor and struggle, family and brotherly bonds, leisure, booze and drugs, lies, schemes, creativity and invention, betrayal, ego, dreams, death. What’s particularly painful about the film is how these nuances are ultimately flattened under the boot of power. The closing scene is a voice-over by the man who was murdered declaring that “They pit the lifers against the new boys, the young against the old, the black against the white. Everything they do is to keep us in our place.”

Today, the expression of power as seen in Schrader’s late 1970s Detroit has itself become a thing of the past. If only “the man” was still the individual boss, union rep, or cop. With capitalist, corporate, state power consolidated and depersonalized, its force is more like gravity than a boot. Brazelton observes these current conditions and contradictions of the “post-industrial,” “post-globalized,” “post-Black,” “late-capitalist,” uniquely American consumerist malaise, angst, betrayal, pain. He doesn’t look away. Synthesizing from these sources, the work is precise in its references and execution yet abstract, even playful, in its presentation. In a balance of vitality, restraint, strength, spontaneity, and grace, the artist manages to make something beautiful out of what he sees. He summons a sense of lively expression hidden in there, a dark humor that merges with the abstraction.

[1] Jerry Bartowski played by Harvey Keitel, Blue Collar, 1978. Directed by Paul Schraeder.

[2] Patton Oswalt, introduction to Blue Collar Criterion release.